Whitehead, Ennis Clement, nickname “Ennis the Menace” born 03-09-1895, in Westphalia, Kansas  the eldest of three children of J. E. Whitehead, a farmer, and his wife Celia.

the eldest of three children of J. E. Whitehead, a farmer, and his wife Celia.

Ennis was married to Mary Morse, born Nicholson Whitehead (1896–1975)  and the couple had one daughter and one son, Margaret Whitehead Hinsch (1921–1999)

and the couple had one daughter and one son, Margaret Whitehead Hinsch (1921–1999)  and Ennis Clement Whitehead Jr (1926–2023)

and Ennis Clement Whitehead Jr (1926–2023)

Ennis was educated at Glenwood District School and Burlington High School. In 1914, he entered the University of Kansas,  intending to obtain a law degree.

intending to obtain a law degree.

Whitehead entered the Army as a flying cadet on 16-08-1917. From June 1917 until November 1917 he was stationed at Chanute Field, Ill., where he was commissioned a first lieutenant in the Aviation Section of the Signal Officers Reserve Corps  on 20-11-1917. Ennis trained as an aviator and served in France, where he was posted to the 3d Aviation Instruction Center and became a qualified test pilot. After the first war, Whitehead returned to school at the University of Kansas.

on 20-11-1917. Ennis trained as an aviator and served in France, where he was posted to the 3d Aviation Instruction Center and became a qualified test pilot. After the first war, Whitehead returned to school at the University of Kansas.

Whitehead was demobilized from the Army in January 1919, and returned to the University of Kansas, earning a Bachelor of Engineering degree in 1920. After graduation, he took a job with The Wichita Eagle  as a reporter in order to earn enough money for law school. In the end though, he decided that he preferred flying. He applied for a commission in the Regular Army, and was re-commissioned as a first lieutenant in the Air Service, on 11-09-1920. On 25-09-1920, he married Mary Nicholson, whom he had known while at the University of Kansas. They had two children: a daughter, Margaret, born in 1921, who later became a lieutenant in the United States Air Force, and a son, Ennis C. Whitehead Jr., who was born in 1926 and graduated from West Point in 1948.

as a reporter in order to earn enough money for law school. In the end though, he decided that he preferred flying. He applied for a commission in the Regular Army, and was re-commissioned as a first lieutenant in the Air Service, on 11-09-1920. On 25-09-1920, he married Mary Nicholson, whom he had known while at the University of Kansas. They had two children: a daughter, Margaret, born in 1921, who later became a lieutenant in the United States Air Force, and a son, Ennis C. Whitehead Jr., who was born in 1926 and graduated from West Point in 1948.

Pan American Flyers receive Distinguished Service Cross certificates from President Calvin Coolidge

Pan American Flyers receive Distinguished Service Cross certificates from President Calvin Coolidge  centre on 02-05-1927. General Brigadier Dargue, Herbert Arthur “Bert”

centre on 02-05-1927. General Brigadier Dargue, Herbert Arthur “Bert”

on the left; Whitehead is second from the left.

on the left; Whitehead is second from the left.

Whitehead was initially stationed at March Field, where he served as a flying instructor. In 1921, he was transferred to Kelly Field where he assumed command of the 94th Pursuit Squadron  of the 1st Pursuit Group.

of the 1st Pursuit Group.  On 20-07-1921, he participated in Brigadier General Billy Mitchell’s

On 20-07-1921, he participated in Brigadier General Billy Mitchell’s  demonstration bombing attack of the ex-German dreadnought Ostfriesland. The 1st Pursuit Group moved to Selfridge Field, Michigan in July 1922. In 1926, Whitehead attended the Air Service Engineering School at McCook Field, graduating first in his class.

demonstration bombing attack of the ex-German dreadnought Ostfriesland. The 1st Pursuit Group moved to Selfridge Field, Michigan in July 1922. In 1926, Whitehead attended the Air Service Engineering School at McCook Field, graduating first in his class.

In December 1926, Whitehead was assigned as the co-pilot for Major Herbert Arthur. Dargue, leading the 22,000-mile (35,000 km) Pan American Good Will Flight touring South America. During a landing at Buenos Aires in March 1927, their aircraft, a Loening OA-1A float plane nicknamed New York,  was involved in a mid-air collision with the Detroit, another OA-1A, forcing both Dargue and Whitehead to bail out. Whitehead suffered only a sprained ankle, but the pilot and co-pilot of the Detroit were killed. The remaining four planes of the flight completed the tour, for which all ten airmen including Whitehead received the first awards of the Distinguished Flying Cross.

was involved in a mid-air collision with the Detroit, another OA-1A, forcing both Dargue and Whitehead to bail out. Whitehead suffered only a sprained ankle, but the pilot and co-pilot of the Detroit were killed. The remaining four planes of the flight completed the tour, for which all ten airmen including Whitehead received the first awards of the Distinguished Flying Cross. ![]()

After three years as an engineering officer with the Air Corps Materiel Division at Wright Field, Ohio, he attended the Air Corps Tactical School at Langley Field from September 1930 to June 1931. While there, he was promoted to captain. Returning to the 1st Pursuit Group, he took command of the 36th Pursuit Squadron. He did staff duty tours at Albrook Field, Panama Canal Zone with the 16th Pursuit Group, at Barksdale Field with the 20th Pursuit Group, and at the headquarters of the General Headquarters (GHQ) Air Force at Langley Field. He was promoted to temporary major in April 1935 and attended the Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth in 1938.

On graduation from the Command and General Staff School, Whitehead was posted to the G-2 (Intelligence) Division of the War Department. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel on 03-12-1940. In February 1941, he was transferred to Luke Field, a new training base, where he was promoted to colonel on 05-01-1942.

In May 1942, Lieutenant General George Howard Brett,

the Allied Air Forces commander in the South West Pacific Area (SWPA), lodged a request with Lieutenant General Arnold, Henry Harley “Hap”,

the Allied Air Forces commander in the South West Pacific Area (SWPA), lodged a request with Lieutenant General Arnold, Henry Harley “Hap”,

the Commanding General of the U.S. Army Air Forces, for Whitehead to be sent out in the grade of Brigadier General as a replacement for Brigadier General Harold Huston George “Pursuit” ,

the Commanding General of the U.S. Army Air Forces, for Whitehead to be sent out in the grade of Brigadier General as a replacement for Brigadier General Harold Huston George “Pursuit” ,

who had been killed in an air crash near Darwin, Northern Territory on 29-04-1942. Whitehead was promoted on 16-06-1942, and ordered to the Southwest Pacific. He flew there with Kenneth Newton Walker,

who had been killed in an air crash near Darwin, Northern Territory on 29-04-1942. Whitehead was promoted on 16-06-1942, and ordered to the Southwest Pacific. He flew there with Kenneth Newton Walker,

a bomber expert, who had also recently been promoted to Brigadier General. Arriving in Australia on 11-07-1942, Whitehead was shocked by the confusion and lack of organization he found. The next day, he reported to General Douglas MacArthur

a bomber expert, who had also recently been promoted to Brigadier General. Arriving in Australia on 11-07-1942, Whitehead was shocked by the confusion and lack of organization he found. The next day, he reported to General Douglas MacArthur  at GHQ SWPA in Melbourne; the two men would get along well. MacArthur later praised Whitehead for his “masterful generalship … brilliant judgement and inexhaustible energy”.

at GHQ SWPA in Melbourne; the two men would get along well. MacArthur later praised Whitehead for his “masterful generalship … brilliant judgement and inexhaustible energy”.

At this time, the stocks of the air force in SWPA were low. At the recent Battle of Milne Bay, a Japanese invasion force had managed to sail past all but a few RAAF P-40 Kittyhawk and Lockheed Hudson aircraft, suffering only limited damage. Opinion at MacArthur’s General Headquarters (GHQ) was that “the failure of the Air in this situation is deplorable; it will encourage the enemy to attempt further landings, with the assurance of impunity”. Unable to provide MacArthur with what he most needed—more and better aircraft and the crews to man them—Arnold decided to replace Brett with Major General George Churchill Kenney.  Arnold hoped that Kenney and the two newly minted brigadier generals could make the best use of what was available. Major General George Kenney arrived in the theater on July 28. Kenney knew Whitehead well, having served with him at Issoudun, the Air Corps Tactical School and GHQ Air Force, and had also served with Walker at the Air Corps Tactical School. “I had known them both for over twenty years,” Kenney later wrote. “They had brains, leadership, loyalty, and liked to work. If Brett had had them about three months earlier his luck might have been a lot better.”

Arnold hoped that Kenney and the two newly minted brigadier generals could make the best use of what was available. Major General George Kenney arrived in the theater on July 28. Kenney knew Whitehead well, having served with him at Issoudun, the Air Corps Tactical School and GHQ Air Force, and had also served with Walker at the Air Corps Tactical School. “I had known them both for over twenty years,” Kenney later wrote. “They had brains, leadership, loyalty, and liked to work. If Brett had had them about three months earlier his luck might have been a lot better.”

Kenney assumed command of the Allied Air Forces on August 4. Three days later, he instituted a sweeping reorganization of the Allied Air Forces. The Australian components were assigned to RAAF Command under Air Vice Marshal William Dowling Bostock,

while the American components were consolidated into the reformed Fifth Air Force

while the American components were consolidated into the reformed Fifth Air Force  under Kenney’s personal command. On paper, the organization followed the orthodox pattern, consisting of V Fighter Command under Brigadier General Paul Wurtsmith,

under Kenney’s personal command. On paper, the organization followed the orthodox pattern, consisting of V Fighter Command under Brigadier General Paul Wurtsmith,

V Bomber Command under Walker, and an Air Services Command under Major General Rush Blodget Lincoln.

V Bomber Command under Walker, and an Air Services Command under Major General Rush Blodget Lincoln.

But Kenney realized that he would have to maintain his headquarters near MacArthur’s GHQ, which moved to Brisbane on July 20, while the fighting was thousands of miles away in New Guinea, with the Fifth Air Force’s principal forward bases around Port Moresby. Moreover, Walker’s headquarters was in Townsville, as heavy and medium bombers were based there and only staged through Port Moresby. Accordingly, Kenney appointed Whitehead as deputy Fifth Air Force commander, and commander of the Advanced Echelon (ADVON) in Port Moresby.

But Kenney realized that he would have to maintain his headquarters near MacArthur’s GHQ, which moved to Brisbane on July 20, while the fighting was thousands of miles away in New Guinea, with the Fifth Air Force’s principal forward bases around Port Moresby. Moreover, Walker’s headquarters was in Townsville, as heavy and medium bombers were based there and only staged through Port Moresby. Accordingly, Kenney appointed Whitehead as deputy Fifth Air Force commander, and commander of the Advanced Echelon (ADVON) in Port Moresby.

Building up Allied air power required ingenuity, improvisation, and innovation. Skip bombing was a new tactic adopted by the Fifth Air Force that enabled its bombers to attack ships at low level. The parachute fragmentation (parafrag) bomb gave the light bombers increased accuracy for close air support missions. Although the B-25 Mitchell was originally designed to bomb from medium altitudes in level flight, Major Paul Irving “Pappy” Gunn  had additional guns installed in the nose of the aircraft to enable it to perform in a low-level strafing role. Whitehead consistently gave his full support to such innovations.

had additional guns installed in the nose of the aircraft to enable it to perform in a low-level strafing role. Whitehead consistently gave his full support to such innovations.

At the Battle of the Bismarck Sea in March 1943, Whitehead was rewarded with an important victory over the Japanese. The battle caused the Japanese to abandon all further attempts to bring supplies and reinforcements in to Lae by the direct sea route from Rabaul. Whitehead was promoted to Major General on 15-03-1943.

Whitehead’s attitude earned him high marks with the Allied land commanders. Lieutenant General Sir Iven Giffart Mackay,  commander of New Guinea Force, reported on 04-02-1943, that “I have found Brigadier General Whitehead of the USAAF extremely cooperative. In fact there is no question of asking for help—he takes the initiative.”

commander of New Guinea Force, reported on 04-02-1943, that “I have found Brigadier General Whitehead of the USAAF extremely cooperative. In fact there is no question of asking for help—he takes the initiative.”

As the Allied offensive gained steam, Whitehead’s main task was to shift his aircraft forward, advancing the bomb line incrementally towards Japan. When the P-38 Lightning arrived in the theater in late 1942, Whitehead at last received a fighter that could match the Japanese A6M Zero. To speed up the Allied advance, the Fifth Air Force developed a number of technical and tactical innovations that extended the range of its aircraft, thus increasing the distance of each Allied advance, which was dependent on the range of Whitehead’s aircraft.

Whitehead assumed command of the Fifth Air Force in June 1944, although he remained subordinate to Kenney. In the Battle of Leyte, MacArthur attempted to move forward beyond the range of land-based aircraft. A long battle of attrition then began on the ground and in the air, as the Fifth Air Force struggled to gain the upper hand with inadequate numbers of aircraft that could be based on Leyte. Gradually, Whitehead gained the upper hand. He was promoted to Lieutenant General on 05-05-1945.

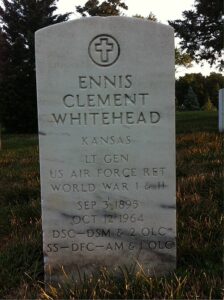

Death and burial ground of Whitehead, Ennis Clement “Ennis the Menace”.

Ennis Whithead passed away of emphysema in Newton, Kansas, on 12-10-1964, age 69, and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery, Section 34, Site 137-A. His son, Ennis Whitehead Jr., later became a Major General in the U.S. Army in the late 1970s, and in March 2003, his grandson Ennis C “Jim” Whitehead III  was promoted to Brigadier General in the Army Reserve, making three generations of general officers.

was promoted to Brigadier General in the Army Reserve, making three generations of general officers.

O

Leave a Reply