Calmeyer, Hans Georg, was born on 23-06-1903 in Osnabrück,  Germany. The son of a judge, he was known in his native city to be an eminent lawyer. When Adolf Hitler‘s NSDAP

Germany. The son of a judge, he was known in his native city to be an eminent lawyer. When Adolf Hitler‘s NSDAP  rose to power in January 1933, Calmeyer was forbidden to practice on suspicion of being “politically unreliable” and engaging in “communist intrigues” (Umtriebe). The latter accusation was based on the fact that Calmeyer had defended communists in court from time to time. While his political worldview was more leftist oriented – although by no means extreme – this was sufficient for the new rulers to brand him as untrustworthy. In May 1940 Calmayer arrived in the Netherlands with the invading forces. A hometown acquaintance offered him to join the occupation administration.

rose to power in January 1933, Calmeyer was forbidden to practice on suspicion of being “politically unreliable” and engaging in “communist intrigues” (Umtriebe). The latter accusation was based on the fact that Calmeyer had defended communists in court from time to time. While his political worldview was more leftist oriented – although by no means extreme – this was sufficient for the new rulers to brand him as untrustworthy. In May 1940 Calmayer arrived in the Netherlands with the invading forces. A hometown acquaintance offered him to join the occupation administration.

In early March 1941, Calmeyer was appointed head of the Entscheidungsstelle (decision-making department) of the Abteilung (department) Innere Verwaltung (Internal Administration) in the occupied Netherlands, where Jews had been required to register since January 1941. It proved possible to submit petitions to Calmeyer’s office on the grounds of doubt about Jewish ancestry. He was responsible for handling these requests for review of registration as Jewish. Especially after the deportations began, more and more applications were submitted, often accompanied by fictitious evidence, to change the registration from ‘full Jew’ to non-Jew, ‘half-Jew’ or ‘quarter-Jew’. This resulted in the creation of the so-called Calmeyer list. He was often willing to grant an exemption in cases of doubt about ancestry. In Nazi worldview of races, the Dutch were considered pure Aryans. The need to purify the Netherlands of alien races therefore became a paramount goal, and a special office, which Calmayer was to head, was established in order to examine doubtful cases so as to decide whether they were to be considered Aryans.

From the moment Calmeyer began his job, on 03-03-1941, Hans realized that it afforded him the – albeit risky – opportunity to help Jews. At the same time, Calmeyer also realized that he would have to act with the utmost care in order to avoid arousing any suspicion within the fiercely antisemitic environment in which he was working. Only to a few carefully selected and reliable confidantes, such as the Dutch lawyer Y.H.M. Nijgh did he voice his profound loathing of National Socialism in general and the persecution of the Jews in particular.

Even so, he avoided any personal contact with lawyers who approached the Generalkommissariat on behalf of Jewish clients, so he would not be suspected of friendliness to Jews (Judenfreundlichkeit). Neither did he ever attempt to intervene personally on behalf of Jews – with the exception of one particular case, his former legal assistant – an attempt that failed.

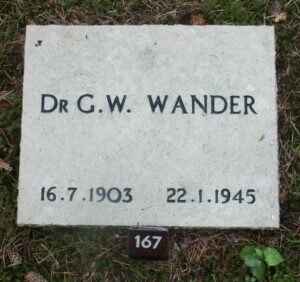

His first move to shield his department from hostile interference was the choice of his coworkers. His direct assistants were the lawyer Dr. Gerard Walter Wander,

this Dutch Resistance man, age 41, was shot when attempting to escape arrest in Amsterdam and Heinrich Miessen, a war-invalid and Sippenforscher (genealogical researcher), and, eventually, the young Dutch lawyer Jacob “Jaap” van Proosdij–all of whom were opposed to the Nazi regime. His office workers, including the secretaries in his department, were also trustworthy. Calmeyer’s bureau was a singular anti-National-Socialist “cell” within the occupation government. Calmeyer’s second step was the creation of a passage through which Jews might be assisted in escaping from the German registration trap. According to the German Nuremberg Laws, membership in a Jewish community was considered proof of a person’s Jewishness. It was a praemissio juris et de jure, i.e., a judicial proposition impervious to proof of the contrary. Only the Führer himself was capable of invalidating a person’s Jewish descent, or, at any rate, deciding that his Jewish background need not be held against him.

this Dutch Resistance man, age 41, was shot when attempting to escape arrest in Amsterdam and Heinrich Miessen, a war-invalid and Sippenforscher (genealogical researcher), and, eventually, the young Dutch lawyer Jacob “Jaap” van Proosdij–all of whom were opposed to the Nazi regime. His office workers, including the secretaries in his department, were also trustworthy. Calmeyer’s bureau was a singular anti-National-Socialist “cell” within the occupation government. Calmeyer’s second step was the creation of a passage through which Jews might be assisted in escaping from the German registration trap. According to the German Nuremberg Laws, membership in a Jewish community was considered proof of a person’s Jewishness. It was a praemissio juris et de jure, i.e., a judicial proposition impervious to proof of the contrary. Only the Führer himself was capable of invalidating a person’s Jewish descent, or, at any rate, deciding that his Jewish background need not be held against him.

Of the total of 5,667 requests submitted to Calmeyer, he made a positive decision in 3,709 cases, which led to the postponement and ultimately the cancellation of deportation. This was life-saving, because the deportation of Jews from the Netherlands to the concentration and extermination camps in Germany and Poland meant death in 96 out of 100 cases on average. He rejected the other 1,958 requests. From there nearly all of them were deported to Auschwitz to be murdered. The overall results of Calmeyer’s interventions were impressive, as the following summary indicates: Out of a total number of 4767, he recognized 2026 as half-Jewish, 873 as Aryans and rejected 1868. For the Jews, Calmeyer had become a household name in those years, and the word “Calmeyeren” was coined.

Death and burial ground of Calmeyer, Hans Georg.

After the war, he was imprisoned by the Allies in Scheveningen from May 1945 to September 1946. He then settled back in Osnabrück, Germany.

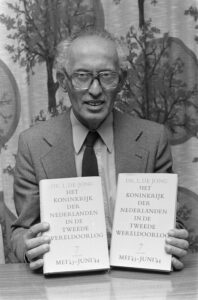

In 1972, Calmeyer died of a heart attack at the age of 69. In 1974, his life story received renewed attention by the Dutch historian De Jong’s  Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de Tweede Wereldoorlog (The Kingdom of the Netherlands in World War II); Calmeyer was posthumously awarded a Yad Vashem medal in 1992. Lawyers IJsbrand Hendrik Martinus (Martien) Nijgh (1992),

Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de Tweede Wereldoorlog (The Kingdom of the Netherlands in World War II); Calmeyer was posthumously awarded a Yad Vashem medal in 1992. Lawyers IJsbrand Hendrik Martinus (Martien) Nijgh (1992),  Van Proosdij (1997), and Adriaan Nicola (Nino) Kotting (2006) received the same award. Nevertheless, Calmeyer’s reputation remained controversial. When his hometown of Osnabrück wanted to name a museum after him in 2020, 200 prominent figures sent a letter of objection to Chancellor Merkel, which was handed over to the embassy on May 28 by former journalist Hans Knoop.

Van Proosdij (1997), and Adriaan Nicola (Nino) Kotting (2006) received the same award. Nevertheless, Calmeyer’s reputation remained controversial. When his hometown of Osnabrück wanted to name a museum after him in 2020, 200 prominent figures sent a letter of objection to Chancellor Merkel, which was handed over to the embassy on May 28 by former journalist Hans Knoop.

Attorney named “Righteous among The Nations” by Yad Vashem for saving Jews in the Netherlands during the Nazi Holocaust in bureaucratic maneuvers. Calmeyer, Hans Georg is buried at the Heger Friedhof, Osnabrück, Stadtkreis Osnabrück, Rheiner Landstraße 168, 49078 Osnabrück, Lower Saxony, Germany.

Leave a Reply